Birmingham (pronounced

/ˈbɜrmɪŋəm/ ( listen) BUR-ming-əm

listen) BUR-ming-əm, locally

[ˈbɜːmɪŋɡəm] BUR-ming-gəm) is a

city and

metropolitan borough in the

West Midlands county of

England. It is the

most populous British city outside

Londonwith a population of 1,030,780 (2010 estimate),

[2] and lies at the heart of the

West Midlands conurbation, the United Kingdom's

second most populous Urban Areawith a population of 2,284,093 (2001 census).

[3] Birmingham's

metropolitan area, which includes surrounding towns to which it is closely tied through

commuting, is also the United Kingdom's

second most populous with a population of 3,683,000.

[4] Birmingham was the powerhouse of the

Industrial Revolution in England, a fact which led to it being known as "the workshop of the world" or the "city of a thousand trades".

[5] Although Birmingham's industrial importance has declined, it has developed into a national commercial centre, being named as the second-best place in the United Kingdom to locate a business.

[6] Birmingham is a national hub for conferences, retail and events along with an established high tech, research and development sector, supported by its three Universities. It is also the fourth-most visited city by foreign visitors in the UK,

[7] has the second-largest city economy in the UK

[8] and is often referred to as the

Second City.

In 2010, Birmingham was ranked as the 55th-most livable city in the world, according to the

Mercer Index of worldwide standards of living.

[9] The

Big City Planis a large redevelopment plan currently underway in the

city centre with the aim of making Birmingham one of the top 20

most liveable cities in the world within 20 years.

[10] People from Birmingham are known as '

Brummies', a term derived from the city's nickname of 'Brum'. This may originate from the city's dialect name,

Brummagem,

[11] which may in turn have been derived from one of the city's earlier names, 'Bromwicham'.

[12] There is a distinctive Brummie

dialect and

accent, both of which differ from the adjacent

Black Country.

GLASGOW:

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Glasgow grew to a population of over one million,and was the fourth-largest city in Europe, after

London,

Paris and

Berlin. In the 1960s, large-scale relocation to

new towns and peripheral

suburbs, followed by successive boundary changes, have reduced the current population of the City of Glasgow unitary authority area to 580,690, with 1,199,629 people living in the

Greater Glasgow urban area. The entire region surrounding the

conurbation covers approximately 2.3 million people, 41% of Scotland's population

Early origins and development:

The present site of Glasgow has been used since prehistoric times for settlement due to it being the furthest downstream

fording point of the River Clyde, at the point of its confluence with the

Molendinar Burn. The origins of Glasgow as an established city derive ultimately from its medieval position as Scotland's second largest bishopric. Glasgow increased in importance during the 10th and 11th centuries as the site of this bishopric, reorganised by King

David I of Scotland and

John, Bishop of Glasgow.

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.

Glasgow grew over the following centuries, the first bridge over the River Clyde at Glasgow was recorded from around 1285, giving its name to the

Briggait area of the city, forming the main North-South route over the river via

Glasgow Cross. The founding of the

University of Glasgow in 1451 and elevation of the

bishopricto become the

Archdiocese of Glasgow in 1492 also increased the town's religious and educational status.

Trading port:

After the

Acts of Union in 1707, Scotland gained trading access to the vast markets of the British Empire and Glasgow became prominent in international commerce as a hub of trade to the Americas, especially in the movement of tobacco, cotton and sugar into the deep water port that had been created by city merchants at

Port Glasgow on the

Firth of Clyde, due to the shallowness of the river within the city itself at that time.

[16] By the late 18th century more than half of the British tobacco trade was concentrated on Glasgow's River Clyde, with over 47 million lbs. weight of tobacco being imported at its peak

Industrialisation:

In its subsequent industrial era, Glasgow produced textiles, chemicals, engineered goods and steel, which were exported. The opening of the

Monkland Canal and basin at

Port Dundas in 1795, facilitated access to the iron-ore and coal mines in

Lanarkshire. After extensive

River engineeringprojects to dredge and deepen the River Clyde as far as Glasgow, shipbuilding became a major industry on the upper stretches of the river, building many famous ships (although many were actually built in

Clydebank). The River Clyde then became an important source of inspiration for artists, such as

John Atkinson Grimshaw, willing to depict the new industrial era and the modern world. Glasgow's population had surpassed that of Edinburgh by 1821. By the end of the 19th century the city was known as the

"Second City of the Empire" and by 1870 was producing more than half Britain's tonnage of shipping

[18] and a quarter of all locomotives in the world.

[19] During this period, the construction of many of the city's greatest architectural masterpieces and most ambitious civil engineering projects, such as the

Loch Katrine aqueduct,

Subway,

Tramway system,

City Chambers,

Mitchell Library and

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum were being funded by its wealth. The city also held a series of

International Exhibitions at

Kelvingrove Park, in

1888, 1901 and 1911, with the

Empire Exhibition subsequently held in 1938.

The 20th century witnessed both decline and renewal in the city. After World War I, the city suffered from the impact of the

Post-World War I recession and from the later

Great Depression, this also led to a rise of radical socialism and the "

Red Clydeside" movement. The city had recovered by the outbreak of

World War II and grew through the post-war boom that lasted through the 1950s. However by the 1960s, a lack of investment and innovation led to growing overseas competition in countries like Japan and Germany which weakened the once pre-eminent position of many of the city's industries. As a result of this, Glasgow entered a lengthy period of relative economic decline and rapid de-industrialisation, leading to high unemployment, urban decay, population decline, welfare dependency and poor health for the city's inhabitants. There were active attempts at regeneration of the city, when the Glasgow Corporation published its controversial

Bruce Report, which set out a comprehensive series of initiatives aimed at turning round the decline of the city. There are also accusations that the

Scottish Office had deliberately attempted to undermine Glasgow's economic and political influence in post-war Scotland by diverting inward investment in new industries to other regions during the

Silicon Glen boom and creating the

new towns of Cumbernauld, Glenrothes, Irvine, Livingston and East Kilbride, dispersed across the

Scottish Lowlands, in order to halve the city's population base.

[20]

However, by the late 1980s, there had been a significant resurgence in Glasgow's economic fortunes. The '

Glasgow's miles better' campaign, launched in 1983, and opening of the

Burrell Collection in 1983 and

Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre in 1985 facilitated Glasgow's new role as a European centre for business services and finance and promoted an increase in tourism and inward investment.

[21] The latter continues to be bolstered by the legacy of the city's

Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988, its status as

European City of Culture in 1990, and concerted attempts to diversify the city's economy.

[22] This economic revival has persisted and the ongoing

regeneration of inner-city areas, including the large-scale

Clyde Waterfront Regeneration, has led to more affluent people moving back to live in the centre of Glasgow, fuelling allegations of

gentrification.

[23] The city now resides in the

Mercer index of top 50 safest cities in the world

[24] and is considered by

Lonely Planet to be one of the world's top 10 tourist cities.

[25] Despite Glasgow's economic renaissance, the East End of the city remains the focus of severe social deprivation.

[26] A Glasgow Economic Audit report published in 2007 stated that the gap between prosperous and deprived areas of the city is widening.

[27] In 2006, 47% of Glasgow's population lived in the most deprived 15% of areas in Scotland,

[27] while the

Centre for Social Justice reported 29.4% of the city's working-age residents to be "economically inactive".

[26] Although marginally behind the UK average, Glasgow still has a higher employment rate than Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester.

[27]

Toponymy

It is common to derive the name Glasgow from the older Cumbric glas cau or a Middle Gaelic cognate, which would have meant green hollow. The settlement probably had an earlier Cumbric name, Cathures; the modern name appears for the first time in the Gaelic period (1116), asGlasgu. However, it is also recorded that the King of Strathclyde, Rhydderch Hael, welcomed Saint Kentigern (also known as Saint Mungo), and procured his consecration as bishop about 540. For some thirteen years Kentigern laboured in the region, building his church at theMolendinar Burn, and making many converts. A large community developed around him and became known as Glasgu (often glossed as "the dear Green" or "dear green place

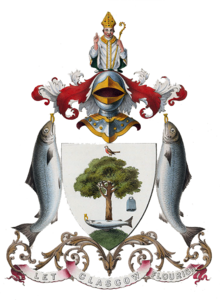

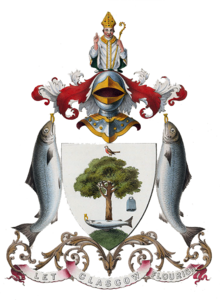

Heraldry

The coat of arms of the City of Glasgow was granted to the royal burgh by the

Lord Lyon on 25 October 1866.

[28] It incorporates a number of symbols and emblems associated with the life of Glasgow's patron saint, Mungo, which had been used on official seals prior to that date. The emblems represent

miracles supposed to have been performed by Mungo and are listed in the traditional rhyme:

-

-

-

- Here's the bird that never flew

- Here's the tree that never grew

- Here's the bell that never rang

- Here's the fish that never swam

-

-

St Mungo is also said to have preached a sermon containing the words

Lord, Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the word and the praising of thy name. This was abbreviated to "Let Glasgow Flourish" and adopted as the city's motto. The motto was more recently commemorated in a song called "Mother Glasgow", which was written by Dundonian singer/songwriter

Michael Marra, but popularised by

Hue and Cry.

In 1450, John Stewart, the first

Lord Provost of Glasgow, left an endowment so that a "St Mungo's Bell" could be made and tolled throughout the city so that the citizens would pray for his soul. A new bell was purchased by the magistrates in 1641 and that bell is still on display in the

People's PalaceMuseum, near

Glasgow Green.

The supporters are two salmon bearing rings, and the crest is a half length figure of Saint Mungo. He wears a bishop's mitre and liturgical vestments and has his hand raised in "the act of

benediction". The original 1866 grant placed the crest atop a helm, but this was removed in subsequent grants. The current version (1996) has a gold

mural crown between the shield and the crest. This form of coronet, resembling an embattled city wall, was allowed to the four area councils with city status.

The arms were re-matriculated by the City of

Glasgow District Council on 6 February 1975, and by the present area council on 25 March 1996. The only change made on each occasion was in the type of coronet over the arms.

[29][30]

Governance:

Industrial action at the shipyards gave rise to the "

Red Clydeside" epithet. During the 1930s, Glasgow was the main base of the

Independent Labour Party. Towards the end of the 20th century it became a centre of the struggle against the

poll tax, and then the main base of the

Scottish Socialist Party, a left unity party in Scotland. The city has not had a

Conservative MP since the

1982 Hillhead by-election, when the SDP took the seat, in Glasgow's wealthiest area: admittedly, the constituency boundaries make it difficult to elect one as the West End is split between two constituencies where its votes are cancelled out by large council estates.

Scottish Parliament region:

The first past the post seats were created in 1999 with the names and boundaries of then existing

Westminster (

House of Commons) constituencies. In 2005, however, the number of Westminster

Members of Parliament (MPs) representing Scotland was cut to 59, with new constituencies being formed, while the existing number of

MSPs was retained at Holyrood.

The ten Scottish Parliament constituencies in the Glasgow electoral region are:

United Kingdom Parliament constituencies

Geography

Glasgow is located on the banks of the

River Clyde, in

West Central Scotland. Its second most important river is the

Kelvin whose name was used for creating the title of

Baron Kelvin and thereby ended up as the

scientific unit of temperature. It is often believed that Glasgow is in Lanarkshire. This is not the case. As already indicated, Glasgow is a unitary authority, and therefore cannot be held to be within any other authority's area. Postal addresses for Glasgow, in common with the rest of Scotland, do not require a "county".

Climate

In spite of its northerly latitude, close to the same line as

Moscow, Glasgow's climate is classified as

Oceanic (

Köppen Cfb). Owing to its westerly position and proximity to the sea, Glasgow is one of Scotland's milder areas. Temperatures are usually higher than most places of equal latitude away from the UK, due to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream.

Winters are normally chilly, damp, and overcast, with a January mean of 4.0 °C (39.2 °F), though lows sometimes fall below freezing. Clear or dry days are rare. Snow occurs but rarely lies in the city centre. The spring months (March to May) are generally mild. Many of Glasgow's trees and plants begin to flower at this time of the year and parks and gardens are filled with spring colours. The summer months (June to September) can vary considerably between mild and wet weather or warm and sunny. The warmest month is usually July, with average highs near 20 °C (68 °F). Autumns are cool to mild, with increasing dampness. Extremes range from -20 to 31.2 °C (-4 to 88 °F), the latter occurring 4 August 1975

Demography

The population of the Glasgow City Council area peaked in the 1950s at 1,200,000 people and before that for 80 years was over 1 million. During this period, Glasgow was one of the most densely populated cities in the world. After the 1960s, clearings of poverty-stricken inner city areas like the

Gorbals and relocation to '

new towns' such as

East Kilbride and

Cumbernauld led to population decline. In addition, the boundaries of the city were changed twice during the late 20th century, making direct comparisons difficult. The city continues to expand beyond the official city council boundaries into surrounding suburban areas, encompassing around 400 square miles (1,000 km

2) of all adjoining suburbs, if commuter towns and villages are included.

There are two distinct definitions for the population of Glasgow: the

Glasgow City Council Area (which lost the districts of

Rutherglen and

Cambuslang to

South Lanarkshire in 1996) and the

Greater Glasgow Urban Area (which includes the conurbation around the city).

In the early 20th century, many

Lithuanian refugees began to settle in Glasgow and at its height in the 1950s there were around 10,000 in the Glasgow area.

[35] Many

Italian Scots also settled in Glasgow, originating from provinces like

Frosinone between Rome and Naples and

Luccain north-west Tuscany at this time, many originally working as "

Hokey Pokey" men.

[36] In the 1960s and '70s, many

Asian-Scots also settled in Glasgow, mainly in the

Pollokshields area. These number 30,000 Pakistanis, 15,000 Indians and 3,000 Bangladeshis as well as

Chineseimmigrants, many of whom settled in the

Garnethill area of the city.

[citation needed] Since 2000, the UK government has pursued a policy of dispersal of

asylum seekers to ease pressure on social housing in the

London area.

Manchester:

Manchester (pronounced

/ˈmæntʃɛstə/ ( listen)

listen)) is a

city and

metropolitan borough of

Greater Manchester,

England. In 2009, the population of the city was estimated to be 483,800,

[2] making it the

seventh-most populous local authority district in England. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest

metropolitan areas; the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester had an estimated population of 2,600,100, the

Greater Manchester Urban Area a population of 2,240,230,

[3] and the

Larger Urban Zone around Manchester, the second-most-populous in the UK, had an estimated population in the 2004

Urban Audit of 2,539,100.

[4] The

demonym of Manchester is Mancunian.

Forming part of the

English Core Cities Group, Manchester today is a centre of the arts, the media, higher education and commerce, factors all contributing to Manchester polling as the

second city of the United Kingdom in 2002.

[7] In a poll of British business leaders published in 2006, Manchester was regarded as the best place in the UK to locate a business.

[8] A report commissioned by Manchester Partnership, published in 2007, showed Manchester to be the "fastest-growing city" economically.

[9] In the

GaWC global city list, Manchester is ranked as a

gamma- world city.

[10] It is the third-most visited city in the United Kingdom by foreign visitors and the most visited in

England outside

London.

[11] Manchester was the host of the

2002 Commonwealth Games, and among its other sporting connections are its two

Premier League football teams,

Manchester City and

Manchester United.

[12]

Etymology

Industrial Revolution

Manchester began expanding "at an astonishing rate" around the turn of the 19th century as part of a process of unplanned

urbanisation[29] brought on by the

Industrial Revolution.

[30] It developed a wide range of industries, so that by 1835 "Manchester was without challenge the first and greatest industrial city in the world."

[27] Engineering firms initially made machines for the cotton trade, but diversified into general manufacture. Similarly, the chemical industry started by producing bleaches and dyes, but expanded into other areas. Commerce was supported by financial service industries such as banking and insurance. Trade, and feeding the growing population, required a large transport and distribution infrastructure: the canal system was extended, and Manchester became one end of the world's first intercity passenger railway—the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Competition between the various forms of transport kept costs down.

[18] In 1878 the

GPO (the forerunner of

British Telecom) provided its first telephones to a firm in Manchester.

[31]

The

Manchester Ship Canal was built in 1894, in some sections by canalisation of the Rivers Irwell and Mersey, running 58 kilometres (36 mi)

[32] from

Salford to Eastham Locks on the tidal Mersey. This enabled ocean going ships to sail right into the Port of Manchester. On the canal's banks, just outside the borough, the world's first industrial estate was created at

Trafford Park.

[18] Large quantities of machinery, including cotton processing plant, were exported around the world.

A centre of capitalism, Manchester was once the scene of bread and labour riots, as well as calls for greater political recognition by the city's working and non-titled classes. One such riot ended with the

Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819. The economic school of

Manchester capitalismdeveloped there, and Manchester was the centre of the

Anti-Corn Law League from 1838 onward.

At that time, it seemed a place in which anything could happen—new industrial processes, new ways of thinking (the

Manchester School, promoting

free trade and

laissez-faire), new classes or groups in society, new religious sects, and new forms of labour organisation. It attracted educated visitors from all parts of Britain and Europe. A saying capturing this sense of innovation survives today: "What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow."

[35] Manchester's golden age was perhaps the last quarter of the 19th century. Many of the great public buildings (including the

town hall) date from then. The city's cosmopolitan atmosphere contributed to a vibrant culture, which included the

Hallé Orchestra. In 1889, when county councils were created in England, the municipal borough became a

county borough with even greater autonomy.

Although the Industrial Revolution brought wealth to the city, it also brought poverty and squalor to a large part of the population. Historian

Simon Schama noted that "Manchester was the very best and the very worst taken to terrifying extremes, a new kind of city in the world; the chimneys of industrial suburbs greeting you with columns of smoke". An American visitor taken to Manchester’s blackspots saw "wretched, defrauded, oppressed, crushed human nature, lying and bleeding fragments".

[36]

The number of

cotton mills in Manchester itself reached a peak of 108 in 1853.

[26] Thereafter the number began to decline and Manchester was surpassed as the largest centre of cotton spinning by

Bolton in the 1850s and

Oldham in the 1860s.

[26] However, this period of decline coincided with the rise of city as the financial centre of the region.

[26] Manchester continued to process cotton, and in 1913, 65% of the world's cotton was processed in the area.

[18] The

First World War interrupted access to the export markets. Cotton processing in other parts of the world increased, often on machines produced in Manchester. Manchester suffered greatly from the

Great Depression and the underlying structural changes that began to supplant the old industries, including textile manufacture.

The Second World War and the Manchester Blitz

Cotton processing and trading continued to fall in peacetime, and the exchange closed in 1968.

[18] By 1963 the port of Manchester was the UK's third largest,

[39] and employed over 3,000 men, but the canal was unable to handle the increasingly large

container ships. Traffic declined, and the port closed in 1982.

[40] Heavy industry suffered a downturn from the 1960s and was greatly reduced under the economic policies followed by

Margaret Thatcher's government after 1979. Manchester lost 150,000 jobs in manufacturing between 1961 and 1983.

[18]

Manchester has a history of attacks attributed to Irish Republicans, including the

Manchester Martyrs of 1867, arson in 1920, a series of explosions in 1939, and two bombs in 1992. On Saturday 15 June 1996, the

Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out the

1996 Manchester bombing, the detonation of a large bomb next to a department store in the city centre. The largest to be detonated on British soil, the bomb injured over 200 people, heavily damaged nearby buildings, and broke windows half a mile away. The cost of the immediate damage was initially estimated at £50 million, but this was quickly revised upwards.

[42] The final insurance payout was over £400 million; many affected businesses never recovered from the loss of trade.

[43]

Large sections of the city dating from the 1960s have been either demolished and re-developed or modernised with the use of glass and steel. Old mills have been converted into modern apartments,

Hulme has undergone extensive regeneration programmes, and million-pound lofthouse apartments have since been developed. The 169-metre tall, 47-storey

Beetham Tower, completed in 2006, is the tallest building in the UK outside London and the highest residential accommodation in western Europe. The lower 23 floors form the Hilton Hotel, featuring a "sky bar" on the 23rd floor. Its upper 24 floors are apartments.

[45] In January 2007, the independent Casino Advisory Panel awarded Manchester a licence to build the only

supercasino in the UK to regenerate the Eastlands area of the city,

[46] but in March the

House of Lords rejected the decision by three votes rendering previous

House of Commons acceptance meaningless. This left the supercasino, and 14 other smaller concessions, in parliamentary limbo until a final decision was made.

[47] On 11 July 2007, a source close to the government declared the entire supercasino project "dead in the water".

[48] A member of the Manchester Chamber of Commerce professed himself "amazed and a bit shocked" and that "there has been an awful lot of time and money wasted".

[49] After a meeting with the Prime Minister, Manchester City Council issued a press release on 24 July 2007 stating that "contrary to some reports the door is not closed to a regional casino".

[50] The supercasino was officially declared dead in February 2008 with a compensation package described by the media as "rehashed plans, spin and empty promises."

[51]

Since around the turn of the 21st century, Manchester has been regarded by sections of the international press,

[52] British public,

[53] and government ministers

[54] as being the

second city of the United Kingdom. A 2007 poll by the

BBC placed it ahead of

Birmingham and

Liverpool in the category of second city of England, but also ahead in the category of

third city. Neither category is officially sanctioned, and criteria for determining what 'second city' means are ill-defined. Manchester is not the second

largest city in terms of

population, but it is argued that cultural and

historical criteria are more important.

[55] The BBC reports that redevelopment of recent years has heightened claims that Manchester is the second city of the UK.

[56] This title however, which is unofficial in the UK, has traditionally been held by Birmingham since the early 20th century.

[57]

Geography

At

53°28′0″N 2°14′0″W

53°28′0″N 2°14′0″W, 160 miles (257 km) northwest of

London, Manchester lies in a bowl-shaped land area bordered to the north and east by the

Pennine hills, a mountain chain that runs the length of

northern England and to the south by the

Cheshire Plain. The

city centre is on the east bank of the

River Irwell, near its confluences with the Rivers

Medlock and

Irk, and is relatively low-lying, being between 115 to 138 feet (35 and 42 m) above

sea level.

[61] The

River Mersey flows through the south of Manchester. Much of the inner city, especially in the south, is flat, offering extensive views from many highrise buildings in the city of the foothills and moors of the Pennines, which can often be capped with snow in the winter months. Manchester's geographic features were highly influential in its early development as the world's first industrial city. These features are its climate, its proximity to a

seaport at

Liverpool, the availability of water power from its rivers, and its nearby

coal reserves.

[62]

The name Manchester, though officially applied only to the metropolitan district of Greater Manchester, has been applied to other, wider divisions of land, particularly across much of the Greater Manchester county and urban area. The "Manchester City Zone", "

Manchester post town" and the "

Manchester Congestion Charge" are all examples of this. The economic geography of the

Manchester City Regionis used to define housing markets, business linkages, travel to work patterns, administrative areas etc.

[63] As defined by

The Northern Way economic development agency the City Region territory encompasses most of the natural economy’s

Travel to Work Area and includes the cities of Manchester and

Salford, plus the adjoining metropolitan boroughs of

Stockport,

Tameside,

Trafford,

Bolton,

Bury,

Oldham,

Rochdale and

Wigan, together with

High Peak (which lies outside the

North West England region),

Cheshire East,

Cheshire West and Chester and

Warrington.

[64]

Manchester experiences a

temperate maritime climate, like much of the

British Isles, with warm summers and cold winters. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year. The city's average annual rainfall is 806.6 millimetres (31.76 in)

[66] compared to the UK average of 1,125.0 millimetres (44.29 in),

[67] and its mean rain days are 140.4 per annum,

[66] compared to the UK average of 154.4.

[67]Manchester however has a relatively high humidity level, which optimised the textile manufacturing (with low thread breakage) which took place there. Snowfalls are not common in the city, due to the

urban warming effect. However, the

Pennine and

Rossendale Forest hills that surround the city to its east and north receive more snow and roads leading out of the city can be closed due to snow.

[68] notably the

A62 road via

Oldham and

Standedge, the

A57 (

Snake Pass) towards

Sheffield,

[69] and the

M62 over

Saddleworth Moor.

liverpool:

Historically a part of

Lancashire, the urbanisation and expansion of Liverpool were both largely brought about by the city's status as a major

port. By the 18th century, trade from the

West Indies, Ireland and

mainland Europe coupled with close links with the

Atlantic Slave Trade furthered the economic expansion of Liverpool. By the early 19th century, 40% of the world's trade passed through Liverpool's docks, contributing to Liverpool's rise as a major city.

Inhabitants of Liverpool are referred to as

Liverpudlians but are also colloquially known as "

Scousers", in reference to the local dish known as "

scouse", a form of stew. The word "

Scouse" has also become synonymous with the Liverpool

accent and

dialect.

[4]Liverpool's status as a

port city has contributed to its diverse population, which, historically, were drawn from a wide range of peoples, cultures, and religions, particularly those from Ireland. The city is also home to the oldest

Black African community in the country and the oldest

Chinese community in Europe.

The popularity of

The Beatles and the other groups from the

Merseybeat era contributes to Liverpool's status as a tourist destination; tourism forms a significant part of the city's modern economy. The city celebrated its 800th anniversary in 2007, and it held the

European Capital of Culture title together with

Stavanger, Norway, in 2008.

[5]

History

King John's

letters patent of 1207 announced the foundation of the borough of Liverpool, but by the middle of the 16th century the population was still only around 500. The original street plan of Liverpool is said to have been designed by King John near the same time it was granted a royal charter, making it a borough. The original seven streets were laid out in a H shape:

- Bank Street (now Water Street)

- Castle Street

- Chapel Street

- Dale Street

- Juggler Street (now High Street)

- Moor Street (now Tithebarn Street)

- Whiteacre Street (now Old Hall Street)

In the 17th century there was slow progress in trade and population growth. Battles for the town were waged during the

English Civil War, including an eighteen-day siege in 1644. In 1699 Liverpool was made a

parish by

Act of Parliament, that same year its first slave ship,

Liverpool Merchant, set sail for Africa. As trade from the

West Indiessurpassed that of Ireland and Europe, and as the

River Dee silted up, Liverpool began to grow. The first commercial

wet dock was built in Liverpool in 1715.

[7][8] Substantial profits from the

slave trade helped the town to prosper and rapidly grow. By the close of the century Liverpool controlled over 41% of Europe's and 80% of Britain's slave commerce.

By the start of the 19th century, 40% of the world's trade was passing through Liverpool and the construction of major buildings reflected this wealth. In 1830, Liverpool and

Manchester became the first cities to have an intercity rail link, through the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The population continued to rise rapidly, especially during the 1840s when

Irish migrants began arriving by the hundreds of thousands as a result of the

Great Famine. By 1851, approximately 25% of the city's population was Irish-born. During the first part of the 20th century, Liverpool was drawing immigrants from across Europe.

Inventions and innovations

Ferries,

railways, transatlantic steamships, municipal trams,

[15] electric trains

[16] and the helicopter

[17] were all pioneered in Liverpool as modes of mass transit.

In the field of public health, the first

lifeboat station, public baths and wash-houses,

[27] sanitary act,

[28] medical officer for health,

district nurse, slum clearance,

[29] purpose-built ambulance,

[30] X-ray medical diagnosis,

[31] school of tropical medicine, motorised municipal fire-engine,

[32] free school milk and school meals,

[33] cancer research centre,

[34] and zoonosis research centre

[35] all originated in Liverpool. The first British

Nobel Prize was awarded in 1902 to

Ronald Ross, professor at the School of Tropical Medicine, the first school of its kind in the world.

[36]Orthopaedic surgery was pioneered in Liverpool by

Hugh Owen Thomas,

[37] and modern medical anaesthetics by

Thomas Cecil Gray.

In finance, Liverpool founded the UK's first Underwriters' Association

[38] and the first

Institute of Accountants. The Western world's first financial derivatives (cotton futures) were traded on the Liverpool Cotton Exchange in the late 1700s.

[39]

Between 1862 and 1867, Liverpool held an annual

Grand Olympic Festival. Devised by

John Hulleyand

Charles Melly, these games were the first to be wholly amateur in nature and international in outlook.

[43][44] The programme of the first modern Olympiad in Athens in 1896 was almost identical to that of the Liverpool Olympics.

[45] In 1865 Hulley co-founded the National Olympian Association in Liverpool, a forerunner of the

British Olympic Association. Its articles of foundation provided the framework for the

International Olympic Charter.

Between 1862 and 1867, Liverpool held an annual

Grand Olympic Festival. Devised by

John Hulleyand

Charles Melly, these games were the first to be wholly amateur in nature and international in outlook.

[43][44] The programme of the first modern Olympiad in Athens in 1896 was almost identical to that of the Liverpool Olympics.

[45] In 1865 Hulley co-founded the National Olympian Association in Liverpool, a forerunner of the

British Olympic Association. Its articles of foundation provided the framework for the

International Olympic Charter.

In 1897, the

Lumière brothers filmed Liverpool,

[47] including what is believed to be the world's first tracking shot,

[48] taken from the

Liverpool Overhead Railway – the world's first elevated electrified railway.

In 1999, Liverpool was the first city outside the capital to be awarded

blue plaques by English Heritage in recognition of the "significant contribution made by its sons and daughters in all walks of life."

[49]

Governance

Liverpool has three tiers of governance; the Local Council, the National Government and the European Parliament. Liverpool is officially governed by a

Unitary Authority, as when

Merseyside County Council was disbanded civic functions were returned to a district borough level. However several services such as the

Police and

Fire and Rescue Service, continue to be run at a county-wide level.

Local Council

The City of Liverpool is governed by

Liverpool City Council, and is one of five metropolitan boroughs that combine to make up the

metropolitan county of

Merseyside. The council consists of 90 elected

councillors who represent local communities throughout the city,

[50] as well as a five man executive management team who are responsible for the day to day running of the council.

[51] Part of the responsibility of the councillors is the election of a council leader and Lord Mayor. The council leader's responsibility is to provide directionality for the council as well as acting as medium between the local council, central government and private & public partners.

[52] The Lord Mayor acts as the 'first citizen' of the city and is responsible for promoting the city, supporting local charities & community groups as well as representing the city at civic events

[53] The current council leader is

Joe Anderson, and current

Lord Mayor is Councillor

Mike Storey.

[54]

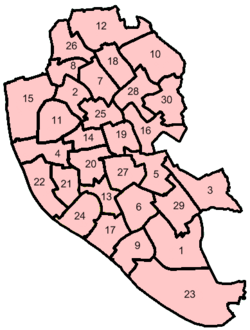

For local elections the city is split into 30 local council wards,

[55] which in alphabetical order are:

In February 2008, Liverpool City Council was revealed to be the worst-performing council in the country, receiving just a one star rating (classified as inadequate). The main cause of the poor rating was attributed to the council's poor handling of tax-payer money, including the accumulation of a £20m shortfall on Capital of Culture funding.

Parliamentary constituencies and MPs

Liverpool has four

parliamentary constituencies entirely within the city, through which

Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected to represent the city in

Westminster:

Liverpool Riverside,

Liverpool Walton,

Liverpool Wavertree and

Liverpool West Derby.

[59] At the

last general election, all were won by Labour with representation being from

Louise Ellman,

Steve Rotheram,

Luciana Berger and

Stephen Twigg respectively. Due to

boundary changes prior to the 2010 election, the

Liverpool Garston constituency was merged with most of

Knowsley South to form the

Garston and Halewood cross-boundary seat. At the most recent election this seat was won by

Maria Eagle of the Labour Party.

[60]

Geography

Demography

As with other major British cities, Liverpool has a large and diverse population. At the

2001 UK Census the recorded population of Liverpool was 441,900,

[63] while a mid-2008 estimate by the

Office for National Statistics had the city's population as 434,900.

[64] Liverpool's population peaked in 1930s with 846,101 recorded in the 1931 census.

[65] Since then the city has experienced negative population growth every decade, with at its peak over 100,000 people leaving the city between 1971 and 1981.

[66] Between 2001 and 2006 it experienced the ninth largest percentage population loss of any UK

unitary authority.

[67] The "Liverpool city region", as defined by the Mersey Partnership, includes Wirral, Warrington, Flintshire, Chester and other areas, and has a population of around 2 million.

[68]

In common with many cities, Liverpool's population is younger than that of England as a whole, with 42.3 per cent of its population under the age of 30, compared to an English average of 37.4 per cent.

[69] 65.1 per cent of the population is of working age.

[69]

Ethnicity

Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest

Black community, dating to at least the 1730s, and some Black Liverpudlians are able to trace their ancestors in the city back ten generations.

[70] Early Black settlers in the city included seamen, the children of traders sent to be educated, and freed slaves, since slaves entering the country after 1722 were deemed free men.

[71]The city is also home to the oldest

Chinese community in Europe; the first residents of the city's

Chinatown arrived as seamen in the nineteenth century.

[72] The gateway in

Chinatown, Liverpool is also the largest gateway outside of China. The city is also known for its large

Irish and

Welsh populations.

[73] In 1813, 10 per cent of Liverpool's population was Welsh, leading to the city becoming known as "the capital of North Wales".

[73] Following the start of the

Great Irish Famine, two million Irish people migrated to Liverpool in the space of one decade, many of them subsequently departing for the United States.

[74] By 1851, more than 20 per cent of the population of Liverpool was Irish.

[75] At the 2001 Census, 1.17 per cent of the population were Welsh-born and 0.75 per cent were born in the

Republic of Ireland, while 0.54 per cent were born in

Northern Ireland,

[76] but many more Liverpudlians are of Welsh or Irish ancestry.

The thousands of migrants and sailors passing through Liverpool resulted in a religious diversity that is still apparent today. This is reflected in the equally diverse collection of religious buildings,

[77] and two Christian cathedrals.

Christ Church, in Buckingham Road, Tuebrook, is a conservative evangelical congregation and is affiliated with the Evangelical Connexion.

[78] They worship using the 1785 Prayer Book, and regard the Bible as the sole rule of faith and practice.

Liverpool's wealth as a port city enabled the construction of two enormous

cathedrals, both dating from the 20th century. The

Anglican Cathedral, which was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and plays host to the annual

Liverpool Shakespeare Festival, has one of the longest

naves, largest organs and heaviest and highest peals of bells in the world. The

Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral, on Mount Pleasant next to

Liverpool Science Park was initially planned to be even larger. Of Sir Edwin Lutyens' original design, only the crypt was completed. The cathedral was eventually built to a simpler design by Sir Frederick Gibberd; while this is on a smaller scale than Lutyens' original design, it still manages to incorporate the largest panel of

stained glass in the world. The road running between the two cathedrals is called

Hope Street, a coincidence which pleases believers. The cathedral is colloquially referred to as "Paddy's Wigwam" due to its shape

listen) BUR-ming-əm, locally[ˈbɜːmɪŋɡəm] BUR-ming-gəm) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands county of England. It is the most populous British city outside Londonwith a population of 1,030,780 (2010 estimate),[2] and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the United Kingdom's second most populous Urban Areawith a population of 2,284,093 (2001 census).[3] Birmingham's metropolitan area, which includes surrounding towns to which it is closely tied through commuting, is also the United Kingdom's second most populous with a population of 3,683,000.[4]

listen) BUR-ming-əm, locally[ˈbɜːmɪŋɡəm] BUR-ming-gəm) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands county of England. It is the most populous British city outside Londonwith a population of 1,030,780 (2010 estimate),[2] and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the United Kingdom's second most populous Urban Areawith a population of 2,284,093 (2001 census).[3] Birmingham's metropolitan area, which includes surrounding towns to which it is closely tied through commuting, is also the United Kingdom's second most populous with a population of 3,683,000.[4]

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.

There had been an earlier religious site established by Saint Mungo in the 6th century. The bishopric became one of the largest and wealthiest in the Kingdom of Scotland, bringing wealth and status to the town. Between 1175 and 1178 this position was strengthened even further when Bishop Jocelin obtained for the episcopal settlement the status of Royal burgh from King William I of Scotland, allowing the settlement to expand with the benefits of trading monopolies and other legal guarantees. Sometime between 1189 and 1195 this status was supplemented by an annual fair, which survives to this day as the Glasgow Fair.